Overview

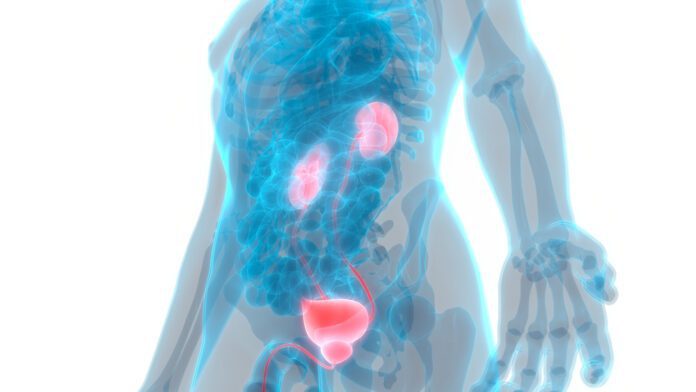

Bladder cancer occurs when there are abnormal, cancerous cells growing uncontrollably in the lining of the bladder, which is the hollow organ in the lower abdomen that stores urine. These cancerous cells begin to affect the normal function of the bladder and can spread to surrounding organs. Bladder cancer is the fourth most common cancer in men, and it is three times more common in men than women.

There are two types of bladder cancer: Nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer, also called superficial bladder cancer, occurs when cancerous cells are contained in the lining of the bladder and have not invaded the bladder wall. This is considered an early stage and represents about 70 to 75 percent of all diagnoses. Muscle-invasive bladder cancer occurs when cancer invades the bladder wall. This is considered an advanced stage and represents the other 25 to 30 percent of diagnoses. In some cases, muscle-invasive bladder cancer can also spread (metastasize) to surrounding organs or other parts of the body.

Cause

Bladder cancer often starts from the cells lining the bladder. These cells are called transitional cells.

These tumors are classified by the way they grow:

• Papillary tumors look like warts and are attached to a stalk.

• Carcinoma in situ tumors is flat. They are much less common. But they are more invasive and have a worse outcome.

The exact cause of bladder cancer is not known. But several things that may make you more likely to develop it include:

• Cigarette smoking — Smoking greatly increases the risk of developing bladder cancer. Up to half of all bladder cancers may be caused by cigarette smoke.

• Personal or family history of bladder cancer — Having someone in the family with bladder cancer increases your risk of developing it.

• Chemical exposure at work — Bladder cancer can be caused by coming into contact with cancer-causing chemicals at work. These chemicals are called carcinogens. Dye workers, rubber workers, aluminum workers, leather workers, truck drivers, and pesticide applicators are at the highest risk.

• Chemotherapy — The chemotherapy drug cyclophosphamide may increase the risk for bladder cancer.

• Radiation treatment — Radiation therapy to the pelvis region for treatment of cancers of the prostate, testes, cervix, or uterus increases the risk of developing bladder cancer.

• Bladder infection — A long-term (chronic) bladder infection or irritation may lead to a certain type of bladder cancer.

Research has not shown clear evidence that using artificial sweeteners leads to bladder cancer.

Symptoms

•Blood or blood clots in the urine

•Pain or burning sensation during urination

•Frequent urination

•Feeling the need to urinate many times throughout the night

•Feeling the need to urinate, but not being able to pass urine

•Lower back pain on 1 side of the body

•The presence of one or all of these signs does not mean you have cancer, but you should be seen by a physician, as these are abnormal bodily functions. Sometimes those diagnosed with bladder cancer do not experience any bleeding or pain.

Treatment

Depending on the stage of cancer and other factors, treatment options for people with bladder cancer can include:

Bladder Cancer Surgery – Surgery is the removal of the tumor and some surrounding healthy tissue during an operation. There are different types of surgery for bladder cancer.

Surgical options to treat bladder cancer include:

• Transurethral bladder tumor resection (TURBT). This procedure is used for diagnosis and staging, as well as treatment. During TURBT, a surgeon inserts a cystoscope through the urethra into the bladder. The surgeon then removes the tumor using a tool with a small wire loop, a laser, or fulguration (high-energy electricity). The patient is given an anesthetic, medication to block the awareness of pain before the procedure begins.

For people with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, TURBT may be able to eliminate cancer. However, the doctor may recommend additional treatments to lower the risk of cancer returning, such as intravesical chemotherapy or immunotherapy (see below). For people with muscle-invasive bladder cancer, additional treatments involving surgery to remove the bladder or, less commonly, radiation therapy are usually recommended.

•Radical cystectomy and lymph node dissection.

A radical cystectomy is a removal of the whole bladder and possibly nearby tissues and organs. For men, the prostate and urethra also may be removed. For women, the uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and part of the vagina may be removed. For all patients, lymph nodes in the pelvis are removed. This is called a pelvic lymph node dissection. An extended pelvic lymph node dissection is the most accurate way to find cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes. Rarely, for some specific cancers, it may be appropriate to remove only part of the bladder, which is called partial cystectomy. However, this surgery is not the standard of care for people with muscle-invasive disease. During a laparoscopic or robotic cystectomy, the surgeon makes several small incisions, or cuts, instead of the 1 larger incision used for traditional surgery. The surgeon then uses telescoping equipment with or without robotic assistance to remove the bladder. The surgeon must make an incision to remove the bladder and surrounding tissue. This type of operation requires a surgeon who is very experienced in minimally invasive surgery. Several studies are still in progress to determine whether laparoscopic or robotic cystectomy is as safe as the standard surgery and whether it can eliminate bladder cancer as successfully as standard surgery.

•Urinary diversion. if the bladder is removed, the doctor will create a new way to pass urine out of the body. One way to do this is to use a section of the small intestine or colon to divert urine to a stoma or ostomy (an opening) on the outside of the body. The patient then must wear a bag attached to the stoma to collect and drain urine.

Surgeons can sometimes use part of the small or large intestine to make a urinary reservoir, which is a storage pouch that sits inside the body. With these procedures, the patient does not need a urinary bag. For some patients, the surgeon can connect the pouch to the urethra, creating what is called a neobladder or “Indiana pouch”, so the patient can pass urine out of the body normally. However, the patient may need to insert a thin tube called a catheter if the neobladder is not fully emptied of urine. Also, patients with a neobladder will no longer have the urge to urinate and will need to learn to urinate on a consistent schedule. For other patients, an internal (inside the abdomen) pouch made of the small intestine is created and connected to the skin on the abdomen or belly button (umbilicus) through a small stoma. With this approach, patients do not need to wear a bag. Patients drain the internal pouch multiple times a day by inserting a catheter through the small stoma and immediately removing the catheter.

Living without a bladder can affect a patient’s quality of life. Finding ways to keep all or part of the bladder is an important treatment goal. For some people with muscle-invasive bladder cancer, treatment plans involving chemotherapy and radiation therapy (see below) may be used as an alternative to removing the bladder.

Therapies using medication

•Systemic therapy is the use of medication to destroy cancer cells. This type of medication is given through the bloodstream to reach cancer cells throughout the body. Systemic therapies are generally prescribed by a medical oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating cancer with medication.

Common ways to give systemic therapies include an intravenous (IV) tube placed into a vein using a needle or in a pill or capsule that is swallowed (orally). Advanced bladder cancer, both muscle-invasive localized disease and metastatic disease, is managed with systemic chemotherapy.

The types of systemic therapies used for bladder cancer include Chemotherapy, Immunotherapy, Targeted therapy.

• Chemotherapy – Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to destroy cancer cells, usually by keeping the cancer cells from growing, dividing, and making more cells. A chemotherapy regimen, or schedule, typically consists of a specific number of cycles given over a set period. A patient may receive 1 drug at a time or a combination of different drugs given at the same time.

•Immunotherapy – Immunotherapy, also called biologic therapy, is designed to boost the body’s natural defenses to fight Also, cancer. It uses materials made either by the body or in a laboratory to improve, target, or restore immune system function. It can be given locally or throughout the body.

•Targeted therapy – Targeted therapy is a treatment that targets, cancer’s specific genes, proteins, or the tissue environment that contributes to cancer growth and survival. This type of treatment blocks the growth and spread of cancer cells while limiting damage to healthy cells.

Not all tumors have the same targets. To find the most effective treatment, the doctor may run tests to identify the genes, proteins, and other factors in the tumor. This helps doctors better match each patient with the most effective treatment whenever possible. Also, research studies continue to find out more about specific molecular targets and new treatments directed at them.

•Radiationtherapy – Radiation therapy is usually not used by itself as a primary treatment for bladder cancer, but it may be given in combination with chemotherapy. Some people who cannot receive chemotherapy might receive radiation therapy alone.

Combined radiation therapy and chemotherapy may be used to treat cancer that is located only in the bladder:

•To destroy any cancer cells that may remain after TURBT, so all or part of the bladder does not have to be removed.

•To relieve symptoms caused by a tumor, such as pain, bleeding, or blockage.

•To treat a metastasis located in 1 area, such as the brain or bone.

Recovery from bladder cancer is not always possible. If cancer cannot be cured or controlled, the disease may be called advanced or terminal.

Other

Exams and Tests

The provider will perform a physical examination, including a rectal and pelvic exam.

Tests that may be done include:

• Abdominal and pelvic CT scan

• Abdominal MRI scan

• Cystoscopy (examining the inside of the bladder with a camera), with biopsy

• Intravenous pyelogram – IVP

• Urinalysis

• Urine cytology

If tests confirm you have bladder cancer, additional tests will be done to see if cancer has spread. This is called staging. Staging helps guide future treatment and follow-up and gives you some idea of what to expect in the future.

The TNM (tumor, nodes, metastasis) staging system is used to stage bladder cancer:

• Ta — The cancer is in the lining of the bladder only and has not spread.

• T1 — cancer goes through the bladder lining but does not reach the bladder muscle.

• T2 — cancer spreads to the bladder muscle.

• T3 — cancer spreads past the bladder into the fatty tissue surrounding it.

• T4 — cancer has spread to nearby structures such as the prostate gland, uterus, vagina, rectum, abdominal wall, or pelvic wall.

Tumors are also grouped based on how they appear under a microscope. This is called grading the tumor. A high-grade tumor is fast growing and more likely to spread.

Bladder cancer can spread into nearby areas, including the:

• Lymph nodes in the pelvis

• Bones

• Liver

• Lungs

Source

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/bladder-cancer

https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bladder-cancer/symptoms-and-signs

https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bladder-cancer/types-treatment

https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/bladder-cancer/types-treatment