Overview of Angina

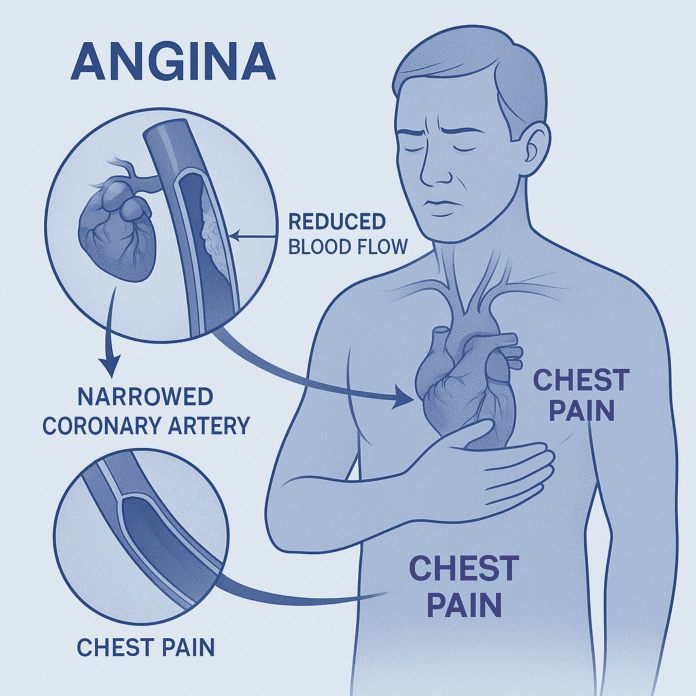

Angina, also known as angina pectoris, is chest pain or discomfort caused by reduced blood flow to the heart muscle (myocardium). It is not a disease itself but a symptom of underlying coronary artery disease (CAD) — the most common form of heart disease. Angina occurs when the heart’s oxygen demand exceeds the oxygen supply delivered by the coronary arteries, typically due to narrowing or blockage from atherosclerosis.

Angina is often described as pressure, squeezing, heaviness, or tightness in the chest, and it may radiate to the shoulders, arms, neck, jaw, or back. Episodes are usually triggered by physical exertion, emotional stress, or cold weather and relieved by rest or medication. Recognizing and managing angina is vital, as it signals increased risk of heart attack and other cardiovascular events.

Commonly Associated With Angina

Angina is strongly linked with conditions and risk factors that contribute to coronary artery disease, including:

- Atherosclerosis – buildup of plaque in coronary arteries (most common cause).

- High blood pressure (hypertension) – damages artery walls.

- High cholesterol – contributes to plaque formation.

- Smoking – accelerates atherosclerosis and reduces oxygen delivery.

- Diabetes mellitus – increases risk of coronary artery disease.

- Obesity and sedentary lifestyle.

- Advanced age – risk increases with age, especially in men over 45 and women over 55.

- Family history of heart disease.

- Emotional stress or sudden temperature changes.

Causes

Angina results from insufficient oxygen delivery to the heart muscle, typically due to reduced blood flow through the coronary arteries. Main causes include:

- Atherosclerosis: Most common cause — fatty plaques narrow coronary arteries, reducing oxygen supply.

- Coronary artery spasm (Prinzmetal or variant angina): Temporary narrowing due to artery spasm, often unrelated to plaque.

- Microvascular dysfunction: Problems in tiny coronary arteries impair blood flow (more common in women).

- Severe anemia or low oxygen levels: Decrease oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood.

- Aortic stenosis or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Structural heart diseases that limit blood supply.

Symptoms

Angina typically causes chest discomfort rather than sharp pain. Symptoms vary by type and may include:

- Pressure, squeezing, heaviness, or burning in the chest

- Pain radiating to the arm, neck, jaw, shoulder, or back

- Shortness of breath

- Nausea or vomiting

- Sweating (diaphoresis)

- Fatigue or weakness

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

Symptoms often occur during exertion or stress and improve with rest or nitroglycerin.

Types of Angina:

- Stable angina: Predictable episodes triggered by activity or stress, relieved by rest or medication.

- Unstable angina: Occurs unpredictably, may happen at rest, lasts longer, and signals an impending heart attack — a medical emergency.

- Variant (Prinzmetal) angina: Caused by coronary artery spasm, often occurs at rest, usually during the night or early morning.

- Microvascular angina: Chest pain due to dysfunction of small coronary vessels, often prolonged and less responsive to nitrates.

Exams & Tests for Angina

Diagnosis involves a detailed history, physical examination, and tests to assess coronary blood flow and heart function:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): Records electrical activity of the heart; may show ischemic changes during angina.

- Exercise stress test: Monitors ECG and heart function during physical exertion.

- Echocardiogram: Evaluates heart muscle function and detects ischemia.

- Coronary angiography: Gold standard; visualizes blockages or narrowing in coronary arteries.

- Coronary CT angiography (CCTA): Noninvasive alternative to assess coronary arteries.

- Blood tests: Check cardiac enzymes to rule out heart attack, and evaluate cholesterol, blood sugar, and other risk factors.

Treatment of Angina

Treatment aims to relieve symptoms, improve blood flow, prevent heart attacks, and reduce disease progression. The approach depends on the type and severity of angina.

1. Lifestyle Modifications:

- Quit smoking and avoid alcohol excess.

- Adopt a heart-healthy diet (low in saturated fats, rich in fruits and vegetables).

- Exercise regularly under medical supervision.

- Maintain healthy weight and manage stress.

- Control blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar.

2. Medications:

- Nitrates (e.g., nitroglycerin): Relieve chest pain by dilating blood vessels.

- Beta-blockers: Reduce heart rate and oxygen demand.

- Calcium channel blockers: Improve blood flow and reduce spasms.

- Antiplatelet agents (e.g., aspirin): Prevent clot formation.

- Statins: Lower cholesterol and stabilize plaque.

- ACE inhibitors or ARBs: Lower blood pressure and reduce heart strain.

- Ranolazine: Used for chronic angina not controlled by other medications.

3. Medical Procedures and Surgery:

- Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI): Balloon angioplasty and stent placement to open narrowed arteries.

- Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG): Surgical creation of alternate pathways for blood flow around blocked arteries.

4. Emergency Care (Unstable Angina):

- Requires hospitalization and urgent evaluation to prevent myocardial infarction.

Source

- Fihn SD, et al. “2014 ACC/AHA/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS Focused Update of the Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Stable Ischemic Heart Disease.” Circulation 2014; 130(19):1749–1767.

- Knuuti J, et al. “2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes.” Eur Heart J 2020; 41(3):407–477.

- Braunwald E. “Stable ischemic heart disease.” Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 21st ed., McGraw Hill, 2022.