Overview of Acute Myeloid Leukaemia in Teenagers and Young Adults

Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) is an aggressive cancer of the blood and bone marrow characterized by the uncontrolled proliferation of immature myeloid cells, called myeloblasts. These abnormal cells accumulate in the bone marrow, crowding out normal blood-forming cells and causing anemia, infection, and bleeding problems.

Although AML is most common in older adults, it also occurs in teenagers and young adults (TYA), typically between 15 and 39 years old, where it often presents with distinct biological features and treatment challenges compared to younger children or older adults. Outcomes for TYA patients have improved significantly with intensive chemotherapy, targeted therapies, and stem cell transplantation, with long-term survival rates approaching 60–70% in favorable-risk cases.

Commonly Associated with Acute Myeloid Leukaemia in Teenagers and Young Adults

Several factors and conditions are associated with the development of AML in the teenage and young adult population:

- Age 15–39 years, with incidence increasing with age.

- Genetic predispositions, such as Down syndrome, Li-Fraumeni syndrome, or familial platelet disorder with RUNX1 mutation.

- Prior cancer treatments, including chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

- Pre-existing bone marrow disorders, such as myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) or myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN).

- Environmental exposures, such as benzene or high-dose ionizing radiation.

- Genetic abnormalities, including t(8;21), inv(16), t(15;17), and mutations in FLT3, NPM1, or CEBPA.

- Lifestyle and health factors, including smoking and obesity, which may influence disease risk and prognosis.

Causes of Acute Myeloid Leukaemia in Teenagers and Young Adults

AML in teenagers and young adults develops when genetic mutations occur in immature myeloid progenitor cells, causing uncontrolled growth and blocking normal maturation. The abnormal myeloblasts accumulate in the bone marrow and peripheral blood, impairing normal hematopoiesis.

Key contributing factors include:

- Chromosomal translocations and gene mutations (e.g., FLT3, NPM1, CEBPA) that disrupt normal cell regulation.

- Inherited predispositions that increase susceptibility to DNA damage.

- Therapy-related AML following prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

- Environmental exposures, such as radiation or industrial chemicals like benzene.

- Spontaneous genetic changes that occur during normal cell division without an identifiable external trigger.

In TYA patients, AML may exhibit more aggressive biology than in younger children, with a higher frequency of adverse-risk genetic mutations and therapy-related AML.

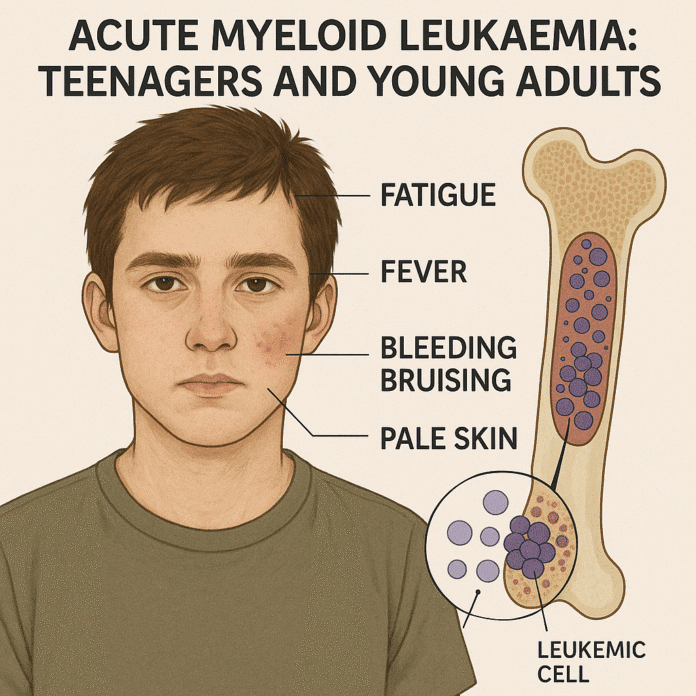

Symptoms of Acute Myeloid Leukaemia in Teens and Young Adults

Symptoms typically develop rapidly over a few weeks and are caused by bone marrow failure and the infiltration of leukemic cells into organs. Common signs and symptoms include:

- Anemia-related: Fatigue, pallor, dizziness, and shortness of breath.

- Low white blood cells: Frequent infections and fevers.

- Low platelets: Easy bruising, petechiae, nosebleeds, or gum bleeding.

- Bone and joint pain: Especially in the legs, hips, and back.

- Swollen gums (gingival hypertrophy): Particularly in monocytic AML subtypes.

- Swelling of liver, spleen, or lymph nodes.

- Unexplained weight loss, night sweats, or fever.

- Neurological symptoms: Headache, confusion, or visual changes if leukemic cells invade the central nervous system.

- Leukostasis symptoms: Shortness of breath or chest pain if white blood cell counts are extremely high.

Because AML progresses quickly, early recognition and prompt treatment are critical.

Exams & Tests for Acute Myeloid Leukaemia in Teens and Young Adults

Diagnosis of AML relies on a combination of blood tests, bone marrow studies, and molecular analyses:

- Complete blood count (CBC): Shows anemia, thrombocytopenia, and abnormal white blood cell counts.

- Peripheral blood smear: Reveals circulating myeloblasts, often with Auer rods.

- Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy: Confirms the diagnosis with ≥20% blasts.

- Immunophenotyping (flow cytometry): Detects myeloid markers such as CD13, CD33, and MPO.

- Cytogenetic and molecular testing: Identifies genetic mutations and chromosomal abnormalities crucial for prognosis and treatment planning.

- Lumbar puncture: Performed if central nervous system involvement is suspected.

- Imaging (e.g., CT or ultrasound): May be used to assess organ infiltration or myeloid sarcomas.

Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukaemia in Teenagers and Young Adults

Treatment for AML in teenagers and young adults is intensive and follows similar principles to adult therapy, though outcomes are generally better in this age group due to better tolerance of high-dose treatments.

1. Induction Therapy

- Goal: Achieve complete remission by eradicating leukemic blasts.

- Standard regimen: “7+3” chemotherapy — cytarabine for 7 days plus an anthracycline (daunorubicin or idarubicin) for 3 days.

- Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), a distinct AML subtype, is treated with all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and arsenic trioxide.

2. Consolidation Therapy

- Goal: Eliminate residual leukemia cells and prevent relapse.

- High-dose cytarabine or additional chemotherapy cycles.

- Allogeneic stem cell transplantation is considered for high-risk patients or those with poor response to induction.

3. Targeted Therapies

- FLT3 inhibitors (e.g., midostaurin, gilteritinib) for FLT3-mutated AML.

- IDH1/IDH2 inhibitors (ivosidenib, enasidenib) for IDH-mutant AML.

- Gemtuzumab ozogamicin, an anti-CD33 monoclonal antibody, in certain AML subtypes.

- BCL-2 inhibitor (venetoclax) combined with chemotherapy in select cases.

4. Supportive Care

- Blood and platelet transfusions.

- Antibiotics and antifungals to prevent infections.

- Management of tumor lysis syndrome and leukostasis.

- Fertility preservation counseling prior to treatment.

5. Stem Cell Transplantation

- Considered for patients with adverse cytogenetics, high-risk features, or relapsed disease.

Overall, long-term survival for TYA AML patients ranges from 55–70% depending on risk profile, genetic mutations, and treatment response.

Source

- Döhner H, et al. “Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations.” Blood 2017; 129(4):424–447.

- Creutzig U, et al. “Acute myeloid leukemia in adolescents and young adults.” Blood 2016; 127(1):59–67.

- National Cancer Institute. “Adolescent and Young Adult Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treatment (PDQ®) – Health Professional Version.” NCI, 2024.