Overview of Blood Poisoning (Sepsis)

Blood poisoning, medically known as sepsis, is a life-threatening systemic response to infection that occurs when the body’s immune system overreacts to an invading pathogen and triggers widespread inflammation throughout the bloodstream. This uncontrolled response can cause organ dysfunction, tissue damage, and, if untreated, septic shock and death.

Sepsis most commonly arises from infections of the lungs, urinary tract, abdomen, or skin, but it can originate from any infection that spreads into the bloodstream. It is a medical emergency — early recognition and rapid treatment are critical for survival.

Commonly Associated with Sepsis

Sepsis is often associated with certain risk factors and conditions that increase susceptibility or severity:

- Severe bacterial infections – the most common cause (e.g., E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae).

- Viral, fungal, or parasitic infections – less frequent but possible causes.

- Hospital-acquired infections – especially in intensive care settings.

- Chronic illnesses – such as diabetes, kidney disease, liver disease, or cancer.

- Weakened immune system – from HIV, chemotherapy, organ transplantation, or immunosuppressive drugs.

- Invasive medical devices – catheters, central lines, ventilators.

- Elderly adults and infants – most vulnerable age groups.

- Recent surgery or trauma.

Causes of Sepsis

Sepsis occurs when an infection spreads beyond its original site and triggers a dysregulated immune response in the bloodstream. Instead of fighting the infection in a controlled way, the immune system releases large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines into circulation, leading to:

- Widespread inflammation (systemic inflammatory response).

- Increased blood vessel permeability, causing fluid leakage and low blood pressure.

- Abnormal blood clotting (coagulopathy), which can block blood flow and damage organs.

- Organ dysfunction and tissue damage from reduced oxygen and nutrient delivery.

Common sources of infection that can lead to sepsis:

- Lungs: Pneumonia

- Urinary tract: Pyelonephritis, urosepsis

- Abdomen: Peritonitis, appendicitis, biliary infections

- Skin: Cellulitis, infected wounds

- Bloodstream: Intravenous line infections or endocarditis

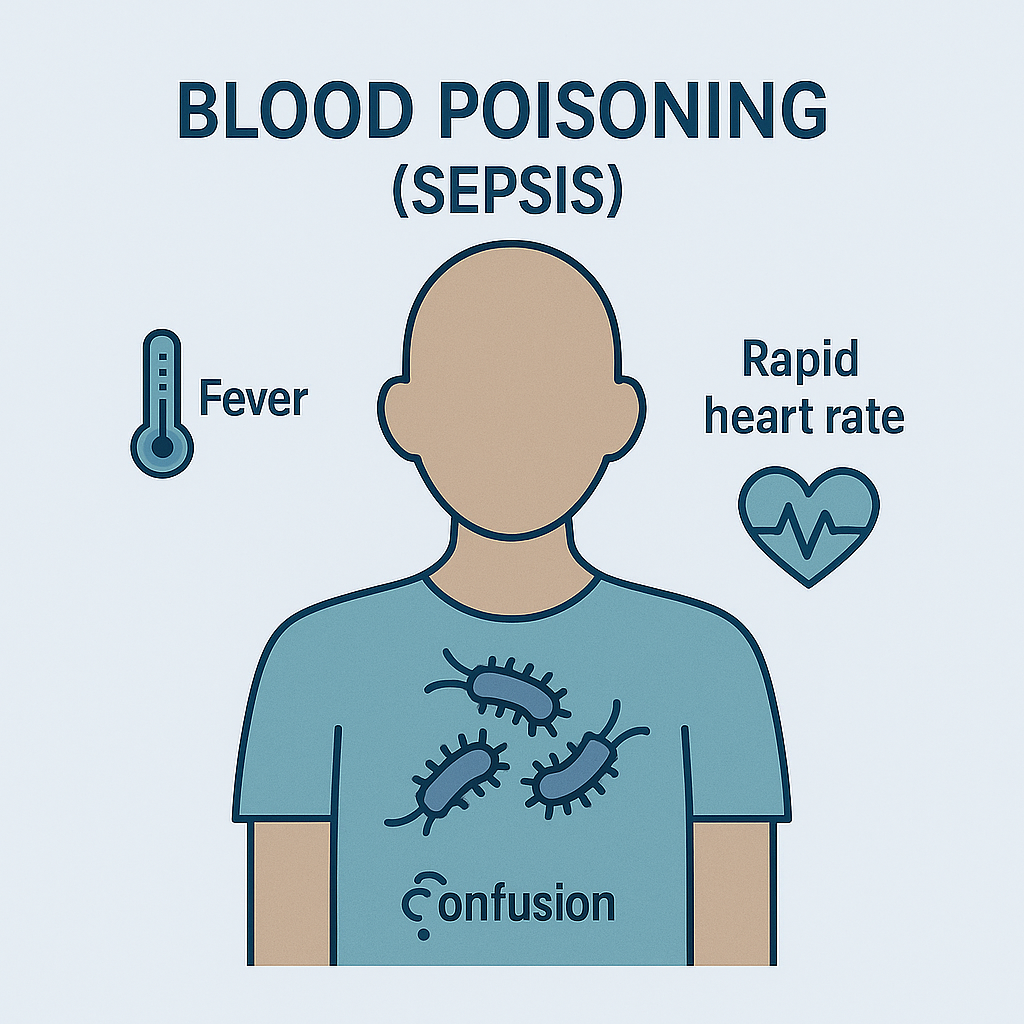

Symptoms of Sepsis

Symptoms can range from mild to severe and progress rapidly. Early recognition is vital.

Early signs and symptoms:

- Fever, chills, or very low body temperature

- Rapid heartbeat (tachycardia)

- Rapid breathing (tachypnea)

- Confusion, disorientation, or altered mental status

- Extreme pain or discomfort

- Sweating and clammy skin

Advanced sepsis (severe sepsis):

- Significant drop in urine output

- Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

- Severe weakness and fatigue

- Bluish or mottled skin

- Organ dysfunction (e.g., kidney or liver failure)

Septic shock (most severe form):

- Critically low blood pressure that doesn’t respond to fluids

- Multi-organ failure

- High risk of death if not treated immediately

Exams & Tests for Sepsis

Rapid diagnosis is essential. There is no single definitive test, so a combination of clinical evaluation, laboratory tests, and imaging is used.

- Physical examination: Check for fever, low blood pressure, rapid pulse, and signs of organ failure.

- Blood tests:

- Complete blood count (CBC): Elevated or decreased white blood cell count.

- Blood cultures: Identify the infecting organism.

- Lactate levels: High levels indicate poor tissue oxygenation.

- C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin: Indicators of systemic inflammation.

- Urine, sputum, or wound cultures: Help locate the infection source.

- Organ function tests: Liver and kidney function panels, arterial blood gases.

- Imaging studies:

- Chest X-ray: For pneumonia.

- Ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI: Identify abscesses, infections, or organ involvement.

Treatment of Sepsis

Sepsis is a medical emergency — treatment must begin immediately, ideally within the first hour of recognition, to reduce the risk of organ failure and death.

1. Immediate Medical Interventions (First Hour Bundle):

- Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics: Started promptly before culture results are available.

- Intravenous fluids: Rapid infusion of crystalloids to restore blood pressure and improve tissue perfusion.

- Oxygen therapy: To ensure adequate oxygen delivery to tissues.

- Blood cultures: Obtained before antibiotics, if possible, without delaying treatment.

2. Advanced Treatments:

- Vasopressors (e.g., norepinephrine): If blood pressure remains low despite fluids.

- Corticosteroids: In some cases to control inflammation and support blood pressure.

- Source control:

- Drain abscesses or infected fluid collections.

- Remove infected catheters or devices.

- Perform surgery if needed (e.g., remove infected tissue or repair perforations).

3. Supportive Care in Intensive Care Unit (ICU):

- Mechanical ventilation: If respiratory failure occurs.

- Renal replacement therapy (dialysis): For kidney failure.

- Nutritional support and glucose control.

4. Long-Term Management:

- Continued antibiotics tailored to identified organisms.

- Rehabilitation for organ damage and recovery from critical illness.

Prognosis:

Early detection and treatment improve survival dramatically. Mortality rates for sepsis range from 10–20%, but can exceed 40–50% in septic shock or multi-organ failure.

Source

- Singer M, et al. “The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3).” JAMA 2016; 315(8):801–810.

- Evans L, et al. “Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2021.” Intensive Care Med 2021; 47(11):1181–1247.

- Fleischmann C, et al. “Assessment of global incidence and mortality of hospital-treated sepsis.” Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 193(3):259–272.