Overview

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) is an enlarged prostate. The prostate goes through two main growth cycles during a man’s life. The first occurs early in puberty when the prostate doubles in size. The second phase of growth starts around age 25 and goes on for most of the rest of a man’s life. BPH most often occurs during this second growth phase.

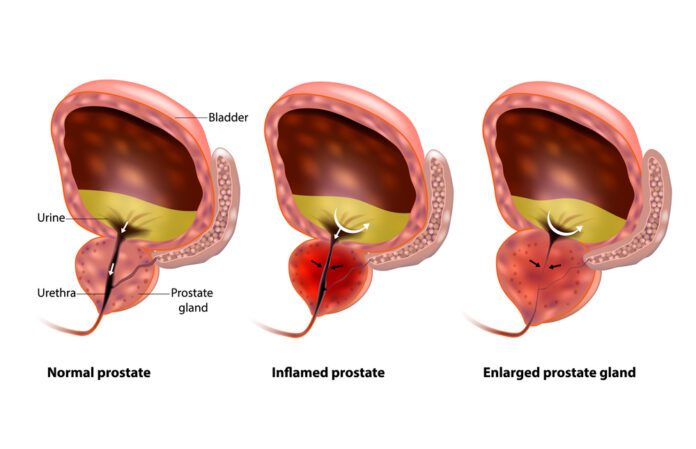

As the prostate enlarges, it presses against the urethra. The bladder wall becomes thicker. One day, the bladder may weaken and may not be able to empty fully, leaving some urine in the bladder. Narrowing of the urethra and urinary retention – not able to empty the bladder fully – causes many of the problems of BPH.

BPH is benign. This means it is not cancer. It does not cause or lead to cancer. But, BPH and cancer can happen at the same time.

What is the Prostate

The prostate is part of the male reproductive system. It is about the size of a walnut and weighs about an ounce. The prostate is found below the bladder and in front of the rectum. It goes all the way around a tube called the urethra, which carries urine from the bladder out through the penis.

The prostate’s main job is to make fluid for semen. During ejaculation, sperm made in the testicles moves to the urethra. At the same time, fluid from the prostate and the seminal vesicles also moves into the urethra. This mixture – semen – goes through the urethra and out through the penis.

BPH is common. About half of all men between ages 51 and 60 have BPH. Up to 90 percent of men over age 80 have it.

Cause

The causes of BPH are not clear. It mainly occurs in older men. Hormone changes are thought to play a role.

Hormones from the testis may be the main factor. For example, as men age, the amount of active testosterone in the blood declines. Estrogen levels stay the same. BPH may occur when these hormone changes trigger prostate cell growth. Another theory is about the role of dihydrotestosterone (DHT). This male hormone supports prostate development. Some studies show that older men have higher levels of DHT. Testosterone levels go down. The extra DHT may cause prostate cell growth.

Symptoms

Since the prostate gland surrounds the urethra (the tube that carries urine outside the body), it is easy to understand that enlargement of the prostate can lead to blockage of the tube.

Therefore, you may develop:

● Slowness or dribbling of the urinary stream.

● Hesitancy or difficulty starting to urinate.

● Frequent urination.

● Feeling of urgency (sudden need to urinate).

● Need to get up at night to urinate.

● Pain after ejaculation or while urinating.

● Urine that looks or smells “funny” (for instance, it’s a different color).

The enlargement of the prostate can lead to blockage of the urethra.

As symptoms get worse, you may develop:

● Bladder stones.

● Blood in the urine.

● Damage to the kidneys from back pressure caused by retaining large amounts of extra urine in the bladder.

If you have any of these symptoms, see the doctor right away:

● Pain in the area of the lower abdomen or genitals while urinating.

● Can’t urinate at all.

● Pain, fever, and/or chills while urinating.

● Blood in the urine.

Treatment

Treatment options for benign prostatic hyperplasia may include

● lifestyle changes

● medications

● minimally invasive procedures

● surgery

A health care provider treats benign prostatic hyperplasia based on the severity of symptoms, how much the symptoms affect a man’s daily life, and a man’s preferences.

Men may not need treatment for a mildly enlarged prostate unless their symptoms are bothersome and affecting their quality of life. In these cases, instead of treatment, a urologist may recommend regular checkups. If benign prostatic hyperplasia symptoms become bothersome or present a health risk, a urologist most often recommends treatment.

Lifestyle Changes

A health care provider may recommend lifestyle changes for men whose symptoms are mild or slightly bothersome.

Lifestyle changes can include:

● reducing intake of liquids, particularly before going out in public or before periods of sleep

● avoiding or reducing intake of caffeinated beverages and alcohol

● avoiding or monitoring the use of medications such as decongestants, antihistamines, antidepressants, and diuretics

● training the bladder to hold more urine for longer periods

● exercising pelvic floor muscles

● preventing or treating constipation

Medications

A health care provider or urologist may prescribe medications that stop the growth of or shrink the prostate or reduce symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Minimally Invasive Procedures

These procedures include

● transurethral needle ablation

● transurethral microwave thermotherapy

● high-intensity focused ultrasound

● transurethral electrovaporization

● water-induced thermotherapy

● prostatic stent insertion

Minimally invasive procedures can destroy enlarged prostate tissue or widen the urethra, which can help relieve the blockage and urinary retention caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Urologists perform minimally invasive procedures using the transurethral method, which involves inserting a catheter—a thin, flexible tube—or cystoscope through the urethra to reach the prostate. These procedures may require local, regional, or general anesthesia. Although destroying troublesome prostate tissue relieves many benign prostatic hyperplasia symptoms, tissue destruction does not cure benign prostatic hyperplasia. A urologist will decide which procedure to perform based on the man’s symptoms and overall health.

Transurethral needle ablation. This procedure uses heat generated by radiofrequency energy to destroy prostate tissue. A urologist inserts a cystoscope through the urethra to the prostate. A urologist then inserts small needles through the end of the cystoscope into the prostate. The needles send radiofrequency energy that heats and destroys selected portions of prostate tissue. Shields protect the urethra from heat damage.

Transurethral microwave thermotherapy. This procedure uses microwaves to destroy prostate tissue. A urologist inserts a catheter through the urethra to the prostate, and a device called an antenna sends microwaves through the catheter to heat selected portions of the prostate. The temperature becomes high enough inside the prostate to destroy enlarged tissue. A cooling system protects the urinary tract from heat damage during the procedure.

High-intensity focused ultrasound. For this procedure, a urologist inserts a special ultrasound probe into the rectum, near the prostate. Ultrasound waves from the probe heat and destroy enlarged prostate tissue.

Transurethral electrovaporization. For this procedure, a urologist inserts a tube-like instrument called a resectoscope through the urethra to reach the prostate. An electrode attached to the resectoscope moves across the surface of the prostate and transmits an electric current that vaporizes prostate tissue. The vaporizing effect penetrates below the surface area being treated and seals blood vessels, which reduces the risk of bleeding.

Water-induced thermotherapy. This procedure uses heated water to destroy prostate tissue. A urologist inserts a catheter into the urethra so that a treatment balloon rests in the middle of the prostate. Heated water flows through the catheter into the treatment balloon, which heats and destroys the surrounding prostate tissue. The treatment balloon can target a specific region of the prostate while surrounding tissues in the urethra and bladder remain protected.

Prostatic stent insertion. This procedure involves a urologist inserting a small device called a prostatic stent through the urethra to the area narrowed by the enlarged prostate. Once in place, the stent expands like a spring, and it pushes back the prostate tissue, widening the urethra. Prostatic stents may be temporary or permanent. Urologists generally use prostatic stents in men who may not tolerate or be suitable for other procedures.

Surgery

For long-term treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia, a urologist may recommend removing enlarged prostate tissue or making cuts in the prostate to widen the urethra.

Urologists recommend surgery when:

● medications and minimally invasive procedures are ineffective

● symptoms are particularly bothersome or severe

● complications arise

Although removing troublesome prostate tissue relieves many benign prostatic hyperplasia symptoms, tissue removal does not cure benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Surgery to remove enlarged prostate tissue includes:

● transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP)

● laser surgery

● open prostatectomy

● transurethral incision of the prostate (TUIP)

A urologist performs these surgeries, except for open prostatectomy, using the transurethral method. Men who have these surgical procedures require local, regional, or general anesthesia and may need to stay in the hospital.

The urologist may prescribe antibiotics before or soon after surgery to prevent infection. Some urologists prescribe antibiotics only when an infection occurs.

Immediately after benign prostatic hyperplasia surgery, a urologist may insert a special catheter, called a Foley catheter, through the opening of the penis to drain urine from the bladder into a drainage pouch.

TURP. With TURP, a urologist inserts a resectoscope through the urethra to reach the prostate and cuts pieces of enlarged prostate tissue with a wire loop. Special fluid carries the tissue pieces into the bladder, and the urologist flushes them out at the end of the procedure. TURP is the most common surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia and is considered the gold standard for treating blockage of the urethra due to benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Laser surgery. With this surgery, a urologist uses a high-energy laser to destroy prostate tissue. The urologist uses a cystoscope to pass a laser fiber through the urethra into the prostate. The laser destroys the enlarged tissue. The risk of bleeding is lower than in TURP and TUIP because the laser seals blood vessels as it cuts through the prostate tissue. However, laser surgery may not effectively treat greatly enlarged prostates.

Open prostatectomy. In an open prostatectomy, a urologist makes an incision, or cut, through the skin to reach the prostate. The urologist can remove all or part of the prostate through the incision. This surgery is used most often when the prostate is greatly enlarged, complications occur, or the bladder is damaged and needs repair. Open prostatectomy requires general anesthesia, a longer hospital stay than other surgical procedures for benign prostatic hyperplasia, and a longer rehabilitation period. The three open prostatectomy procedures are retropubic prostatectomy, suprapubic prostatectomy, and perineal prostatectomy. The recovery period for open prostatectomy is different for each man who undergoes the procedure.

TUIP. A TUIP is a surgical procedure to widen the urethra. During a TUIP, the urologist inserts a cystoscope and an instrument that uses an electric current or a laser beam through the urethra to reach the prostate. The urologist widens the urethra by making a few small cuts in the prostate and the bladder neck. Some urologists believe that TUIP gives the same relief as TURP except with less risk of side effects.

After surgery, the prostate, urethra, and surrounding tissues may be irritated and swollen, causing urinary retention. To prevent urinary retention, a urologist inserts a Foley catheter so urine can drain freely out of the bladder. A Foley catheter has a balloon on the end that the urologist inserts into the bladder. Once the balloon is inside the bladder, the urologist fills it with sterile water to keep the catheter in place. Men who undergo minimally invasive procedures may not need a Foley catheter.

The Foley catheter most often remains in place for several days. Sometimes, the Foley catheter causes recurring, painful, difficult-to-control bladder spasms the day after surgery. However, these spasms will eventually stop. A urologist may prescribe medications to relax bladder muscles and prevent bladder spasms.

Exams and Tests

Your health care provider will ask questions about your medical history. A digital rectal exam will also be done to feel the prostate gland.

Other tests may include:

• Urine flow rate

• Post-void residual urine test to see how much urine is left in your bladder after you urinate

• Pressure-flow studies to measure the pressure in the bladder as you urinate

• Urinalysis to check for blood or infection

• Urine culture to check for infection

• Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test to screen for prostate cancer

• Cystoscopy

• Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine tests

You may be asked to fill out a form to rate how bad your symptoms are and how much they affect your daily life. Your provider can use this score to judge if your condition is getting worse over time.

https://www.urologyhealth.org/urologic-conditions/benign-prostatic-hyperplasia-(bph)

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/9100-benign-prostatic-enlargement-bph

https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/urologic-diseases/prostate-problems/prostate-enlargement-benign-prostatic-hyperplasia